Optimising Federalism

This post follows on from In Support of Federalism. There are many countries around the world that use Federalism as a system of government, and some work better than others. It would be good to improve the standard of democracy around the world, and so i

This post follows on from In Support of Federalism.

There are many countries around the world that use Federalism as a system of government, and some work better than others. It would be good to improve the standard of democracy around the world, and so if any countries were considering becoming federal, it would be good to know what features get the best results. Given an existing federation, any changes will necessarily take a significant amount of time and effort to make, so again, knowing what features get the best results would be very useful in determining what changes to focus on.

Ideally, it would be good to realise all of the benefits listed in the previous two posts - legibility, antifragility, greater freedom, political incubation, a distributed economy, closer proximity to the government and less conflict. What we need is to isolate any factors that get in the way of these benefits, so that existing federations can pursue reforms, and unitary countries can avoid predictable future issues.

So if our aim is to have a well-functioning federation, what do we need to think about regarding the states?

Composition

As is demonstrated in many existing federations - wherever different cultural groups reside in different areas, it is clearly worthwhile to allow them a certain autonomy in their laws and governance. This reduces both the likelihood of oppression, and people’s perception that they are being ruled over by disinterested outsiders. In the modern era however, there is another division that is worth considering.

Rural areas and metropolitan areas have very different requirements, focuses and cultures. It makes sense for significantly different areas to have different rules, and to be independent from each other, as otherwise there will always be a power struggle between the different demographics. Whether it is a case of legislators ignoring rural poverty while they focus on an exciting development in a burgeoning city, or a case of subsidising farmland while neglecting inner city degradation, it is very difficult to represent such different groups simultaneously. This is actually already an issue in the European Parliament where 6 MEPs represent the entirety of Yorkshire and the Humber. The needs of a village in the North York Moors, and the needs of people in inner city Sheffield are very different, and require very different solutions and expertise. A small selection of obvious conflicts are in the table below:

TopicCityCountryHeatingBan wood fires - extensive wood burning causes smog in densely populated areas and cleaner solutions existLimited gas piping - people burn wood as there are few alternativesGunsLittle legitimate need, high riskUseful for pest controlTransportDiscourage cars to ease congestion - public transport is cleaner and more efficientPopulation density is too low for public transport to be economical

A reasonable aim would therefore be for states to be either urban or rural, rather than both. Avoiding states that contain both a very large city and a significant number of rural residents will avoid many of these tensions. The question then becomes where to draw the line - what about a state containing a few small cities and a large rural population?

Due to the way that cities scale, a city of 1 million residents will have far more than double the number of high density inner city residences than a city of 500,000. This suggests that the kind of environments that make cities so different to the countryside are likely to grow superlinearly with the size of the city. Although some tensions are inevitable, this implies that the same number of people that might reside in a large city, but broken up into a number of small cities and towns, could be rolled into largely rural states with much less of a problem. Another mitigating effect of multiple cities and towns is that they would likely be more spread out across the state than a single conurbation, making more of the rural population near to a town or city, reducing the cultural gap further. Whilst it depends heavily on the size of state that is being sought, a reasonable rule of thumb would be that once a city is large enough to form its own state, it should probably be carved out to avoid these conflicts. This would mean that people in the countryside in the vicinity of a major conurbation would not find themselves hugely outvoted by the city dwellers.

This goes against the current make-up of US states, many of which are a mixture of large cities and very rural areas. No US states have a population density over 1000 people per square kilometre - although there are several very rural states with no large cities, there are no states with large cities that do not have substantial rural populations as well. In states such as New York, California and Illinois, the rural population is smaller than the urban population, resulting in their wishes and concerns often being ignored, whilst in states such as Texas and Georgia, despite the huge cities of Houston, Dallas and Atlanta, the rural population is larger than the urban population, resulting in the urban population's wishes and concerns being ignored instead.

There are two different justifications for this set-up that are often given - the US's voting system and the ability for a state to be independently self-sustaining, but these are not particularly compelling reasons:

In the US voting system the senate and presidency are heavily influenced by state borders - the senate gets 2 senators per state, each elected on a first past the post basis, so that even a large minority within a state may get no representation in the senate. The Electoral College system of voting for the presidency works on a similar, “winner gets all” basis within most states. This means that the rural minority in California, and the urban minority in Texas effectively get no say in the senate or presidency. In theory, in a state split very close to 50/50, this could be fair, as a small shift in appeal one way or another would swing the state, however most states are not like this, and even if a state was, it may not last due to population migrations towards or away from cities.

Due to the particular voting systems used, suggestions of having urban states in the US runs into accusations of “gerrymandering state borders”, however this is not a problem if the voting system used does not depend on these borders. Although the voting system will be difficult to change in the US, there is no reason why any other country must replicate their system. A nationwide election i.e. the presidency, could be done on the total national vote of a country, with no distinction between voters from different states. An election of representatives meanwhile, i.e. the senate, could be done using one of many systems of proportional representation. Therefore, on a national level the state borders don’t need to affect anything politically, but on a state level, internal similarities can reduce governmental tension and deadlock.

Regarding the other justification, of the need for states to be independently self-sustaining, there are good arguments for a country itself to have this ability. By being self-sustaining, a country's fragility to external events such as food or energy shortage and war is reduced. Within a country however, this argument is less persuasive - states are able to work together, and the federal government should facilitate this.

Unless a state is entirely surrounded by a single other state, with no coastline, it has options of which other states it wants to work together with. Obviously such a situation is worth avoiding when setting up states within a federal system, just in case, but even then, the role of the federal government should mitigate this. Even at a national level, places like Singapore and Hong Kong have been extremely successful whilst having little rural land, having to rely on trade to source the basics of survival. Although this is quite a fragile situation for a country, it is clearly not necessarily detrimental, and this risk should be much reduced for a state within a federation.

Population Size

Too much variation in the size of different states makes federal governance difficult. Either large states get disproportionate sway, or small states are overrepresented. Attempts can be made to find a balance between these effects in such a way that they cancel each other out, but this is very difficult. In the complex real world of politics, this often just means that both issues exist simultaneously in different areas.

The state of California makes up about an eighth of the population of the US and about a sixth of its economy, making its state government hugely and disproportionately influential both culturally and economically. In the senate however, their 39 million residents have the same two senators as Wyoming’s 580,000. For the House of Representatives, an attempt is made to distribute representatives fairly evenly by population, using a method that CGP Grey explains very thoroughly in this video, but this is only one of many spheres of influence that the state has, and even this method of representation is not conclusively fair.

Note that I am not claiming that California is systematically overpowered or systematically underpowered. Depending on the area in question it may be one or the other, but to such a significant extent that regardless of how well you try to balance these opposing effects, there will be people whose voices remain unheard in the realm that they care about.

Similarly, within the EU, Germany makes up just under a fifth of the population of the EU and just over a fifth of its economy - an even more outsized influence. Within the EU, many countries and citizens feel that Germany sets the direction of the EU to far too great an extent, due to its economic clout. On the flip side, in the European Parliament, the smallest member state of Malta gets 6 members out of the total of 705, or slightly under 1%, despite having just over one thousandth of the EU population.

Clearly, attempts have been made to make these systems fair, but such wildly different sizes of states makes this effectively impossible. Far better, would be to limit the sizes of states to be within a certain range of population. This raises the question, what is the best size for a state to be, and how wide should this range be?

Upper Estimate

Let’s start with finding an upper estimate for the target size of states - the largest population that can be dealt with as a single state before significant issues start cropping up. The more populous a state is, the more difficult and complex it is to administer. This complexity introduces fragility to the state itself, but a large state can also reduce the antifragility of the country as a whole, as there are fewer states, which means fewer entities trying different strategies. Another issue with large states is again that of representation - it is harder for politicians to be in touch with the people, so it feels less democratic. This suggests that a good approach for placing an approximate upper bound on the size a state can be whilst being well run, is finding how well it can perform the job of politically representing its populace.

In order to do this, firstly we need to know the maximum number of people per representative - the largest number of people that a single person can effectively represent. How to find this is not obvious, but we can work through two possible metrics for determining this. These are very rough - effectively Fermi estimates, but that should give us somewhere to start:

Whilst arguably not essential, it would be good for a representative to be able to address all of their constituents in person. This would mean being able to host all of their constituents in a location to give a speech or rally. A large stadium is not strictly necessary for this, but more people than would fit into a large stadium would be difficult to host in an alternative location. A large stadium tends to have a capacity of between 40,000 and 90,000 people, so one estimate for the maximum number of people per representative can be between 10,000 and 100,000 people.

Similarly whilst they might not actually do this, it would be good for a representative to be able to meet all of their constituents in a given year. There are about 1,700 working hours per year, and if you spent every minute of this meeting a different person, that would allow you to meet 102,000 people. This is a bit extreme, as even the most in-touch representative would be unlikely to spend more than half of their time doing this, and 5 minutes is really the bare minimum to actually have a constructive, informative conversation with someone. These assumptions reduce it down to 10,200 people, so we are again left with a maximum number of people per representative of between 10,000 and 100,000 people.

We can compare this with how real countries represent their populaces. India has 790 representatives across both parts of their bicameral legislature. With a population of 1.24 billion, this means that there is 1 representative per 1.56 million people. On the other end of the spectrum is Nauru, whose 19 member parliament represents their 9,500 strong population, giving 500 people per representative. Looking across all of the 200 or so countries in the world, it can be seen that the median and mean of people per representative are 36,000 and 72,000 respectively. These values are reassuringly within the estimates that we found above.

The next thing we need is to estimate how large a parliament/state legislature can be before it becomes dysfunctional. For this, we can use Dunbar’s number, which is a theoretical upper limit on the number of people with whom one can maintain stable social relationships. This is a reasonable number to use, as it is useful for representatives to be able to know and interact with every other representative, in order to successfully navigate the process of drafting legislation.

Dunbar’s number is estimated to be between 100 and 290, with the most common estimates being around 150. Again, real legislatures range from 741 representatives for the EU parliament to 14 representatives for the small island nation of St Kitts & Nevis. The median and mean of legislature sizes are 120 and 180 respectively. We can use these numbers to give us a range of estimates for where the upper estimate of the ideal size of a state might be.

10,000 people per representative times 100 representatives gives us 1,000,000 people - not so much an upper estimate, but a fairly reasonable number of people in a state.

100,000 people per representative times 290 representatives gives us 29,000,000 people - an upper bound that pushes all of the considerations above to their limits. Germany and California are both well above this, but if we are looking to suggest a kind of “best practice” for the size of states, it might do to be a little more conservative.

Taking the geometric mean of both 10,000 with 100,000 and 100 with 290, we get 32,000 people per representative and 170 representatives. This gives us 5,440,000 people in a state - comparable with Slovakia or South Carolina.

Taking further inspiration from existing countries, we can review which countries are particularly well run. Large entities are more complex, and therefore more difficult to run, so although a small country or state can still be run badly, a large country or state is less likely to be run well. We can reasonably expect to see a range of sizes of entities being run poorly, but only relatively small entities being run well.

The Democracy Index consists of 5 components that measure aspects of democracy. These aspects range from the electoral process itself to the political culture. All of them are important, but the one most relevant to finding the ideal size of state for a government to function well is unsurprisingly called “Functioning of Government”. Looking at the top scoring countries by this metric can give us further insight into what sizes of country or state allow for a well run government. For this, I will split federal countries into their component states, as this is the entity that we want to judge.

The top scoring countries for Functioning of Government, all scoring 9.64/10 are:

CountryLargest Federal SubdivisionPopulationCanadaOntario13,000,000Sweden10,000,000Norway5,300,000

The next group scoring 9.29 are:

CountryLargest Federal SubdivisionPopulationNetherlands17,000,000Denmark5,800,000New Zealand4,700,000SwitzerlandZürich1,500,000Iceland340,000

Remaining countries scoring >8.5 are:

CountryLargest Federal SubdivisionPopulationChile19,000,000GermanyNorth Rhine-Westphalia18,000,000AustraliaNew South Wales8,000,000BelgiumFlemish Region6,500,000Finland5,500,000Uruguay3,400,000Luxembourg600,000

In the group of countries scoring >8, we finally get a large non-federal country. This is Japan, with a population of 127m. Despite not being federal however, in Japan 70% of government expenditure is administered locally, which is more than many federal countries. This means that although the central government has the power to take back control of this expenditure (a power it might not have in a federal country), it is reasonable to treat Japan's provinces as states for the purposes of comparing how well the government functions:

CountryLargest Applicable SubdivisionPopulationTaiwan24,000,000JapanTokyo14,000,000Estonia1,300,000Mauritius1,200,000Malta440,000

Finally when the score drops below 8, we encounter entities that have populations over 25 million. There are many small entities too, as expected, but we now start to see large countries that are generally considered successful, despite frequent complaints about poor governance.

CountryFoG ScoreLargest Applicable SubdivisionPopulationSouth Korea7.8651,000,000France7.5065,000,000UK7.50England55,000,000Portugal7.5038,000,000US7.14California39,000,000

Although it is not particularly statistically rigorous and there are many other variables that confound the data, we can at least observe that all countries with Functioning of Government score greater than 8 consist of entities that have a population less than 25 million. With these 20 high scoring countries, if we split the federal (or functionally federal) countries into their constituent states, we get a list of 127 entities (113 states and 14 unitary countries). As already noted, the largest of these is Taiwan with a population of 24 million, whilst the smallest is the canton of Switzerland called Appenzell Innerrhoden with a population of 16,000. Unsurprisingly, a large number of these entities are really quite small, so the median size of these 127 entities is 1.4 million, whilst three quarters of them are smaller than 4 million.

The largest gives us a similar number to before for an upper bound, but we are still looking for a sensible statistic to inform a more modest recommendtion for how populous an ideal state might be able to be. Whilst larger than the median, the mean of this selection is still quite small at 3.1 million, due to the large number of very small entities. We can instead use the RMS, which weights larger entities more, as they have more people in them. The RMS of the population of these entities is 5.2 million.

We now have a couple of different estimates for upper limits on how populous we might want states to be in an ideal world, so we can turn our attention to the other end of the scale.

Lower Estimate

Small states have their own problems that are very different to those of large states. There is a higher administrative overhead for small states, as governments have certain relatively fixed costs that do not vary significantly as the size of the state changes. This is very similar to the pressure on companies to grow and merge in order to find economies of scale. In the extremes, very small states can be too small to run their own services effectively, needing to pool resources with other states or get federal help. There is also a greater risk of regulatory capture, as a smaller government is generally more easily bought or influenced than a larger one. These issues suggest that an approximate lower bound for state size might be found by investigating the necessary economies of scale in government functions.

An obvious place to start, where economies of scale are very important is healthcare. For this rough estimate, I will use UK figures and terminology, as it is what I am familiar with and the UK has a fairly functional health system, so it shouldn’t be too far off.

When splitting a country into states, it would be sensible if each state had a large enough population to warrant a hospital with a Major Trauma Centre (one with operating theatres and the necessary equipment to deal with emergencies and serious trauma cases). The smallest Major Trauma Centre in the UK is in Newcastle with 620 beds (most have between 800 and 1200 beds), but in order to get people to hospital quickly, governments would usually aim to have more coverage across an area than a single hospital, so you would generally see multiple smaller hospitals and at least one large one in any particular region. To comfortably meet this, it would be sensible to aim for a large enough population to support a minimum of double this (1,240 beds at a bare minimum, or more conservatively around 2,000 beds).

Across the OECD, the number of hospital beds per 1,000 people ranges from 1.5 to 13 with the median around 4. Taking the German figure of 8 beds per 1,000 people, we would need a population of 155,000 to warrant the provision of 1,240 beds. With only 2 beds per 1,000 people, if we targeted 2,000 beds we would need a population of 1,000,000.

Alternatively, we can look at policing. Avoiding corruption is important, so as a bare minimum, you need some form of “internal affairs” that can police the police. Of course, this could be done at a federal level, but a state having its own (effective) internal affairs department is beneficial for its autonomy. Having more than 5% of police being internal affairs would be egregiously inefficient, so we can use 5% as a rough estimate. At the same time, we can use Dunbar’s number again - in order to avoid corruption within internal affairs, it would be good to have enough people that everyone can’t know everyone else. This implies that we want at least Dunbar’s number of police officers in a state’s internal affairs department.

The number of police officers per 100,000 population varies between countries - Canada, Sweden, Switzerland, England, Australia and the US have around 200 police officers per 100,000, Belgium, France and Germany have around 350, but Uruguay, Spain and Russia have 500-600. With these numbers, we can again produce a range of estimates for how few people could live in a state before particular problems might start to arise:

If we assume Dunbar’s number is 100, we would need 2000 police to give us 100 internal affairs officers if they made up 5% of the force. If we had 600 police per 100,000 people, we would then need a population of 330,000 to justify the requisite number of police.

Taking the other extreme, we can assume Dunbar’s number is 290, and that we need only 200 police per 100,000 people. This means we would need 5,800 police officers, which would require a population of 2.9 million.

In the middle, if we again assume Dunbar’s number is 170, and that we need 350 police per 100,000 people, we need 3,400 police officers, requiring a population of 0.97 million.

Sensible Size Range

These estimates are just that - estimates. There is nothing fundamental stopping a smaller or a larger population from being governed well. It is evidently possible for large, highly centralised states with over 50 million people to do quite well and be considered democratic, as evidenced by France and South Korea, whilst a small state of 50,000 people could have a Major Trauma Centre if it wanted, regardless of cost or efficiency concerns. Furthermore, just as states could rely on federal police to operate an internal affairs unit, states could pool their resources and open a major hospital jointly. The objective here is simply to make it easier. By reducing the number of hurdles to overcome for a government to be effective and democratic, it becomes more likely that any given government will achieve this. These numbers therefore help to give us some bounds on the question of what a sensible size is for a state:

Political representation gives us a “best practice” upper estimate of 5.44 million, and an upper bound of 29 million.

Existing well run countries and states give us a median of 1.4 million, an indicative size of 5.2 million and an upper bound in the region of 25 million.

Healthcare gives us a “best practice” lower estimate of 1 million, and a lower bound of 155,000.

Policing tells us that 2.9 million is probably a very reasonable size, gives us a “best practice” lower estimate of 0.97 million and a more aggressive lower estimate of 330,000.

With these, we can round the numbers a bit, to produce a fairly reasonable rule of thumb. In an ideal world, to stand the best chance at avoiding the problems mentioned above, states should range in size from a population of 800,000 to a population of 6.4 million. This would also then mean that no state was more than 8 times the size of any other, which would make political representation much easier to keep fair, as well as keeping the differences in economic clout much more manageable.

Of course, this range might not suit every country, so a wider range is also possible to produce. A quarter of the bottom of the range, and four times the top of the range gives us 200,000 and 25.6 million - both in line with the more extreme numbers above. It would not be sufficient to have states ranging in size from 200,000 to 25.6 million however, as this would allow the largest to be as much as 128 times the size of the smallest. Better would be to limit states within a country to a smaller range within this, in which no state can be more than 8 times the size of the smallest.

Why 8 times? You may ask. Keeping states' populations within a factor of 2 of each other would surely be even better... The issue is one of practicality. Splitting a country into divisions that seem relatively natural is essential for giving its constituent states a feeling of legitimacy. Often pre-existing political borders make up the borders of a state, or natural features such as rivers or mountains form natural dividing lines. By forcing states into too small of a size range, you lose flexibility to draw borders in appropriate places, and risk people feeling that they were arbitrary or artificial, leading to lower public engagement with the state institutions.

Another practical consideration is that populations can change significantly over time. As an example, between 1850 and 1950 the population of the Borough of Birmingham in the UK went from 200,000 to 1 million - a five-fold increase in 100 years. With an acceptable population range that was too small, any rapid demographic shift would give rise to significant bureaucracy and political wrangling on a regular basis, as states had to be split or merged multiple times per century.

Ultimately, there is no concrete reason why the number should be exactly 8. It happens to be the approximate difference in size between the upper and lower "best practice" estimates above, and it is a nice round number. It allows a state at the bottom end of the range to double in size three times before hitting the top end of the range. Alternatively, a state with a population at the geometric mid-point could halve or double in size, and still have wiggle room for further population variation before running up against the limits. This flexibility seems beneficial, whilst a much wider range starts to raise questions again of how to ensure fairness between states of vastly differing sizes.

This proposal would mean that countries could choose any of these ranges of population, when setting the upper and lower limits on state populations:

Lower LimitGeometric Mid-pointUpper Limit200,000560,0001,600,000300,000840,0002,400,000400,0001,120,0003,200,000600,0001,680,0004,800,000800,0002,240,0006,400,0001,200,0003,360,0009,600,0001,600,0004,480,00012,800,0002,400,0006,720,00019,200,0003,200,0008,960,00025,600,000

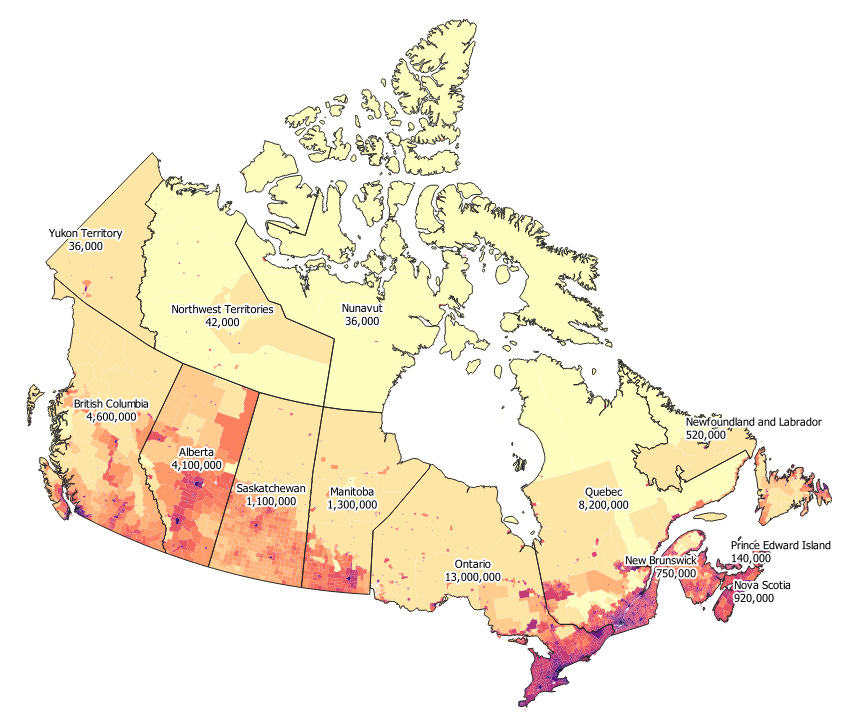

Given that population is not the only relevant dimension to consider here, the fact that this process leads us to a range of recommendations, rather than just a single one is quite useful. A country that is very sparsely populated might choose to use smaller state populations, to keep the physical dimensions of states more manageable, or a more densely populated country might choose the range of larger state populations to avoid having to divide cities up into too many parts. Canada for example currently has several territories that are very large geographically, but that have a tiny population. To achieve a population of 200,000 would require Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Nord-du-Quebec, Labrador, and Divisions 22 and 23 of Manitoba combined. India by contrast has a current population of 1.35 billion people, so even splitting it into the minimum number of states, each with a population very near 25.6 million, they would have 53 states.

Of federal countries that currently exist, only Nigeria and Austria have a range of state sizes that actually satisfy this. Nigeria’s smallest top level administrative unit is the Federal Capital (population 1.4 million) and its largest is Kano (population 9.4 million) - 6.7 times the size. Austria’s smallest state is Burgenland (population 290,000) and its largest is Vienna (population 1.9 million) - 6.6 times the size.

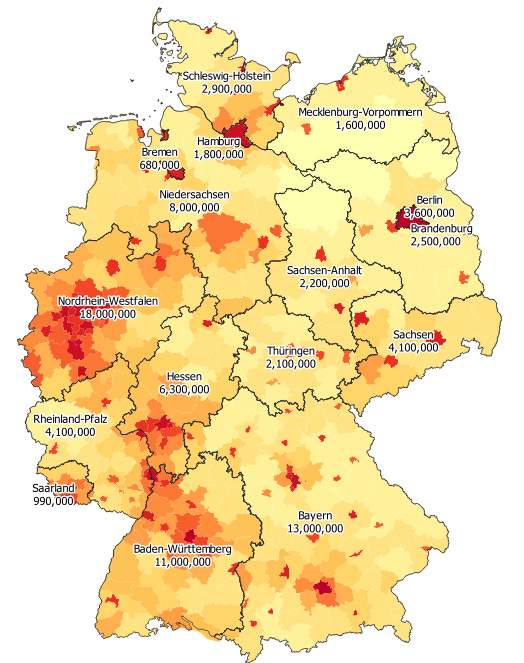

Mexico, Japan, Malaysia and Germany are all close-ish, with their largest states being 22.5 times, 23.6 times, 24 times and 26.4 times the size of their smallest states respectively. This sounds a long way off, but often there are outliers at both ends of the scale. In Germany the largest state of North Rhine-Westphalia has over 26 times the population of the smallest state of Bremen, but the second largest state of Bavaria actually only has just over 8 times the population of the third smallest state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.

German States with their Populations

Colours represent population density by census area (darker is more dense)

This is all a far cry from the US, where California has over 67 times the population of Wyoming, the EU, where Germany has over 174 times the population of Malta, or India, where Uttar Pradesh has 327 times the population of the state of Sikkim. In fact, if you count India’s territories too (districts that are directly administered by the federal government), it is even worse - Uttar Pradesh has 3125 times the population of Lakshadweep. The territory of Lakshadweep still has a representative in the lower house (Lok Sabha) which when compared with Uttar Pradesh’s 80 representatives makes their votes 39 times as powerful.

Subsequent Border Changes

All of these ideas around composition and size of states are all very well, but part of the point of federal systems is that the central government cannot unilaterally make changes like that. Because the goal here is a federal (rather than simply devolved) system of government, there must be a well defined process, and an element of consent on behalf of the state. This means that If there is a target size for states, a concrete plan is needed in advance for what happens when populations change over time. In an existing federation, this process would need to be added to the constitution or equivalent, which could be politically difficult or take time, however for a country considering becoming federal, this would simply be one of the many considerations that would need to be made during that process.

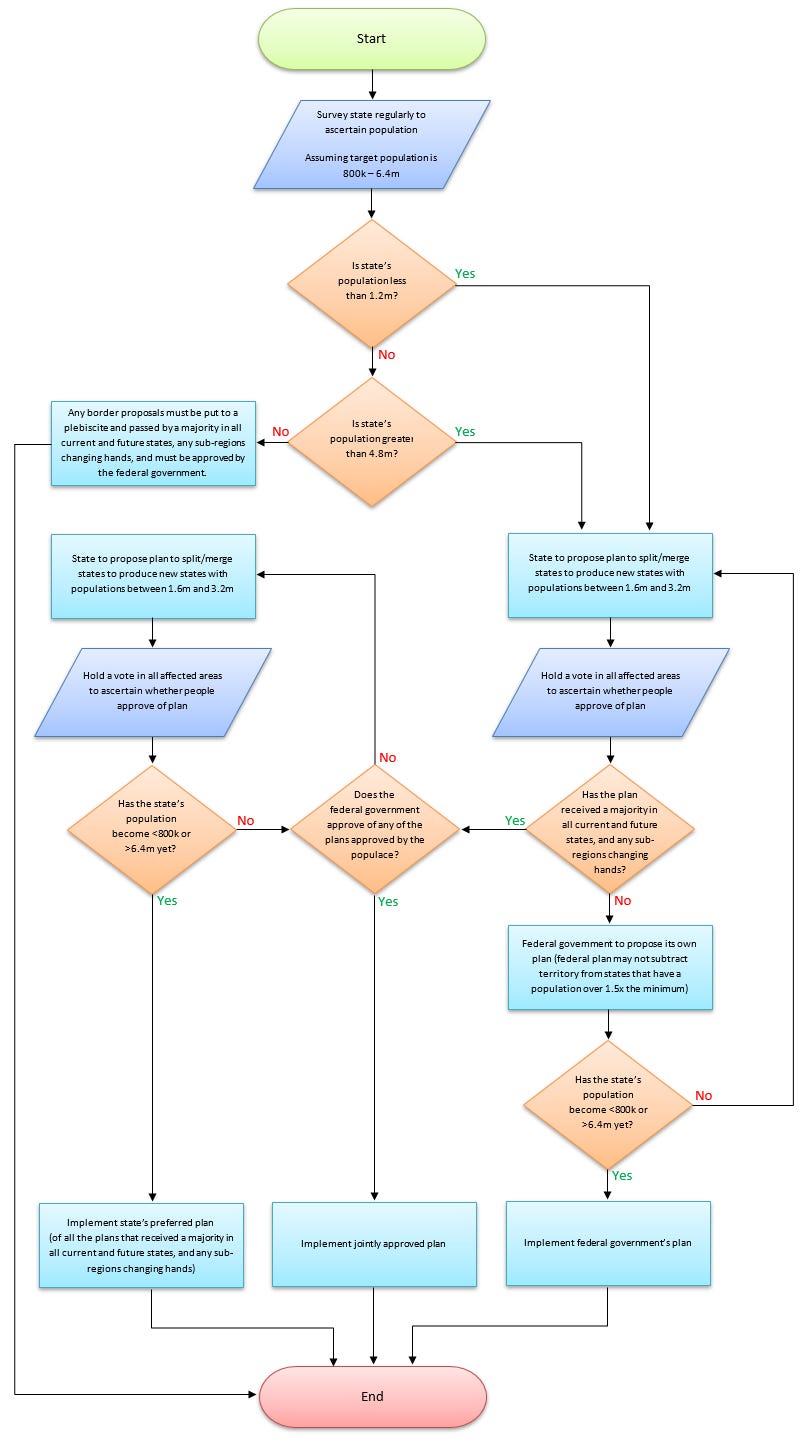

My proposal for a process that tries to maximise the autonomy of states, whilst still ensuring that the federal government can keep states to within the given size range is as follows, and would kick in when any state’s population shrinks to 1.5x the minimum or grows to 0.75x the maximum population size.

For states over 0.75x the maximum:

The state can propose a border line/division. This doesn't necessarily have to be a division that splits the state in two - to be valid, a plan just has to create states that are between 2x the minimum and 0.5x the maximum. This is to avoid the successor states having to undergo this process again too soon. For example, if the country’s target size for states is 800,000 - 6,400,000 (differing by a maximum of a factor of 8), this process would trigger when the population of a state went over 4,800,000, and a valid proposal would suggest successor states ranging from 1,600,000 and 3,200,000 people.

The State's plan would then be put to a plebiscite, and would need to be approved by a majority in each newly proposed state. If the plan involved border changes with another state, this plan would also need to be approved by that state and any sub-regions that were changing hands.

If this succeeds one of two things can happen:

If the federal government agrees with the proposal, it can be implemented immediately.

If the federal government disagrees, new border proposals can be made, either by the state or the federal government. At this point though, whilst the federal government can make proposals, it cannot implement them unilaterally - it is up to the state to accept a proposal and put it to the vote. If any proposal receives the approval of both the affected populace and the federal government, it can be implemented immediately.

If nothing is able to be implemented, this process can continue until the state’s population tips over the maximum. Once this happens, one of two things can happen:

If a plan has passed the plebiscite, it will be implemented immediately, regardless of the federal government’s objections. If multiple plans were voted on and approved, whichever of the plans is the state’s preferred option can be implemented.

If no plans passed the plebiscite, the federal government’s preferred plan will be implemented immediately.

For states under 1.5x the minimum, a similar process can apply, but state will need to negotiate with other states for merging/splitting:

If all affected states agree and a plebiscite passes in all current and newly proposed states, similarly either the federal government can agree immediately, or it will automatically happen when the population tips under the minimum.

If the plebiscite does not pass or states cannot reach an agreement, the federal government can again make its own proposal, however its proposal may not subtract territory from states that have a population over 1.5x the minimum. Because this proposal will be the default plan if nothing passes the vote, it cannot adversely affect any other states - it can only add territory to them.

At any other time, states should also be able to propose adjustment of their borders, with the agreement of other states affected. If these changes get the same approval from their populace and from the federal government, they can occur. If these twin approvals are not achieved though, changes should not occur to any state’s borders unless its population has tipped above or below the limits, or it is a state gaining or ceding territory to another state in a chain of territory exchanges that directly involves a state whose population is outside the limits.

This can all be visualised as a flowchart (using the 800k-6.4m range as an example):

This effect of all of this should be to give states an incentive to think ahead, and get their population's buy in to any boundary changes. It should generally result in the populations of states remaining within the desired bounds without infringing significantly on their autonomy, but enables the country to avoid permanent deadlock if the state is dysfunctional.

Subdivisions & Consistency

Because of the autonomy that states enjoy within a federal system, there is nothing stopping a small region within a state from being semi-autonomous with respect to the state itself. This means that if an area has a particularly unique character, but is too small to be viable as a state, the state containing it could simply grant it greater autonomy than it otherwise might have. This avoids the federal government having to interact directly with such a small entity, whilst still allowing very small populations to have a reasonable level of freedom and independence.

Some good examples of where this would be appropriate are places like Nunavut in Canada, the Shetland and Orkney Islands in the UK or Lakshadweep in India. As remote regions with low populations, they will not come anywhere close to the minimum populations given above. At the same time though, their remoteness means that wherever the state government is situated, it will still run into issues of proximity, with politicians struggling to remain in touch with the populace. The remoteness will also give these populations unique concerns that risk being overlooked by the state government if the population is an insignificant portion of a larger state.

Canadian Provinces and Territories with their Populations

Colours represent population density by census area (darker is more dense)

For such (admittedly rare) occurrences, something akin to a federation of districts within a state would be appropriate, ensuring that regardless of the state’s politics, these remote places and populations have sufficient autonomy. This then avoids the inefficiency of the national government having to deal directly with the governments of tiny populations and keeps the number of types of domestic entity that the federal government has to deal with to a minimum.

The direct administration of Washington D.C. by the US government, or the different status of Canadian territories compared with provinces are all areas where people have to navigate multiple rules for how different levels of government interact. By ensuring a consistent relationship between states and the federal government, a lot of complexity can be avoided, which makes governing easier, but also improves legibility.

State Representation

The US senate used to be indirectly elected - senators were appointed by state legislatures. The House of Representatives has always been directly elected, giving people a vote on someone to represent them at the national level, but the senators were there to represent the states. This made the two bodies very different - the decisions people make when electing their state legislature are more localised than those made when electing federal representatives. This meant that the state’s appointees would have different goals and considerations, making the senate an important balance against the power of the federal legislators.

This was changed in 1913 with the 17th amendment to the constitution, making senators directly elected. Whilst some could see this as a victory for democracy, it makes the house of representatives and the senate very similar. Federal concerns can now sway the electorate in both chambers of the legislature, reducing the importance of more local issues in the federal government.

It is understandable that a group of politicians appointing their own representative might make people uncomfortable, however the system pre-1913 allowed for senators to act in the best interest of their states without necessarily succumbing to the winds of populism. The divisive national issues of the day could be debated in the House of Representatives without consuming all deliberations, allowing other necessary governing to be done. Something like this sounds desirable, but raises the question of how to go about generating such a body of people that have national influence, but that can be elected based on local concerns and interests. Avoiding the elections of these people from becoming just another chance to focus myopically on the national wedge issues is difficult once it becomes known that they might wield power at a national level.

One alternative to having their elections be one step removed from the populace, as with the US system pre-1913, would be to have this national power be a secondary role that is eclipsed by the importance of their state role. Whilst no guarantee, this would make it far more likely that people would be concerned with state issues over national issues when voting. State Governors are a possibility here - it is a position that is fundamentally focused around the state, and it is sufficiently important that it is unlikely to be overshadowed by national issues.

In the past, this would not have been a possibility, as each state Governor would have needed to spend the vast majority of their time in their state, making national issues a distraction, and precluding the possibility of spending significant time in the national capital. With the advent of telephones and the internet however, there is no need for them to be physically present. If necessary, they could send delegates to the capital to research and negotiate on their behalf, but the final decision in any vote could still rest with them. As long as state Governors were directly elected, this “Council of Governors” would then be a directly elected body, reducing concerns about lack of democracy.

Summary

Federalism seems like a promising route towards improving the standard of democracy around the world. For any country considering becoming a federation, it will be desirable for them to benefit from all of the positives of federalism whilst avoiding the pitfalls that have caused problems elsewhere. To make good democratic governance as easy and likely as possible, the following points summarise the recommendations from the sections above:

Composition - encourage states to split large conurbations from rural areas to improve the state government's ability to effectively govern.

Relative size - limit state sizes so that the most populous state can be no larger than 8 times the population of the least populous state.

Absolute size - avoid states having populations outside of the range from 200,000 to 25.6 million.

Adjustment - have a constitutional or federal mechanism for adjusting the borders of states when they reach these limits (that empowers the states to offer their own solutions, rather than providing the federal government with undue power over them).

Subdivisions - avoid top-level exceptions - if smaller autonomous regions are beneficial, states can always devolve power further.

Representation - give elected state officials a forum at the federal level so that local concerns can be addressed without being overshadowed by national politics (obviously, this is in addition to national representatives, not instead of them).