Arguments for a UBI - The Accountant

This post is part of the sequence Arguments for a Universal Basic Income. Simple Tax Code In countries that try to have a progressive tax system, income taxes can be exceedingly complicated. The tendency is to try not to tax people very much when they are

This post is part of the sequence Arguments for a Universal Basic Income.

Simple Tax Code

In countries that try to have a progressive tax system, income taxes can be exceedingly complicated. The tendency is to try not to tax people very much when they are earning less than a certain amount, then to increase the percentage that their income is taxed at, as that income increases. This is seen as preferable to taxing everyone at the same rate, as although 20% of a £10,000 income is much less than 20% of a £100,000 income, that £2,000 is essential for the first person to be able to eat, whereas the person earning £100,000 could spare a lot more than £20,000 before even noticing the difference.

To take the UK as an example, in the 2018-19 tax year, the first £11,850 of your annual income is not taxed, then anything received above that is taxed at 20%. Anything above £46,350 had an additional 20% tax applied (called the 40% or higher rate band), and anything above £150,000 had a further 5% applied (called the 45% or additional rate band). This is further complicated by the fact that for every £2 of income over £100,000 that you earned, you lose £1 of the tax free £11,850, which is then taxed at 40%, resulting effectively in any income between £100,000 and £123,700 being taxed at an additional 20% (a notional 60% band).

Finally, to make matters even more confusing, there is Employee’s National Insurance – an income tax in all but name, which is an additional 12% on any income between £8,400 and £46,350, and an additional 2% on anything above that. Expressed in a table, this looks as follows:

Lower Income ThresholdUpper Income ThresholdIncome Tax RateNI RateCombined Tax Rate Applied Within Band£0£8,4000%0%0%£8,400£11,8500%12%12%£11,850£46,35020%12%32%£46,350£100,00040%2%42%£100,000£123,70060%2%62%£123,700£150,00040%2%42%£150,000+45%2%47%

There are a great many resources such as online tax calculators that help to make sense of all of this, but what I am interested in here is the "effective tax rate", that is, if you were to apply the same rate to all of your income to come up with your tax bill, what would that rate be.

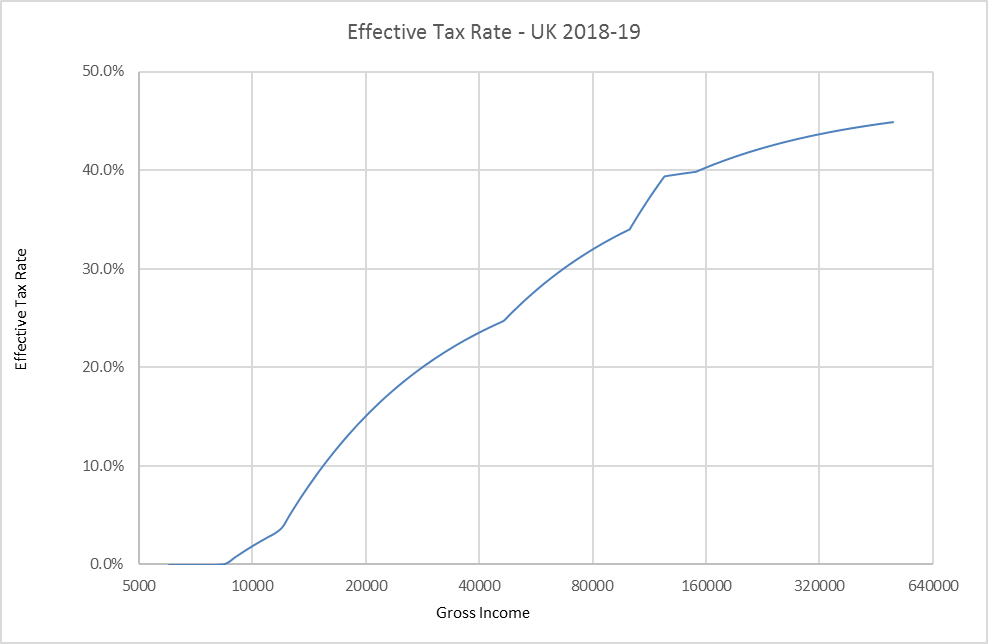

The results of the UK income tax code are shown as a blue line on the graph below (plotted on a logarithmic x-axis – doubling with each successive gridline rather than increasing a fixed amount, so that it is easier to see the detail):

The gross income is the amount paid before tax, and the impact of the thresholds mentioned above, mean that someone earning £20,000 per year will pay £3,022 in tax, for an effective tax rate of 15.1%, while someone earning £80,000 will pay £25,587 in tax, for an effective tax rate of 32.0%. The strange kinks in the line are a direct result of the discontinuities in the tax bands, but the intention is clear – to tax higher earners at a higher rate than lower earners, this being the definition of a progressive tax.

Whilst much simpler, clearly taxing everyone at the top rate of 47% (45% plus 2% National Insurance) on all their income is not ideal, as this would be an enormous financial burden on people with lower incomes, and would be a huge tax increase for everyone except people earning well into the seven figures. What happens when we combine it with a Universal Basic Income however?

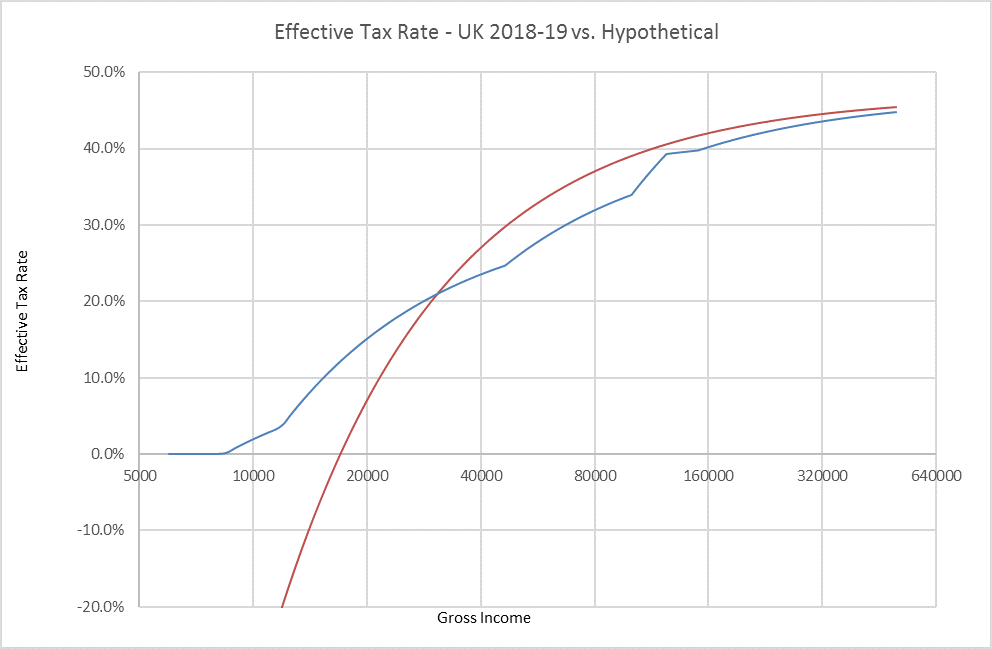

The red line on the graph below shows the effective tax rates under a hypothetical tax code which taxes all earned income at 47%, but also pays a Universal Basic Income of £8,000 per annum. As you can see, rather than a flat line across the top at 47%, which would be the result without a Universal Basic Income, the combined effect of a flat tax rate and a Universal Basic Income gives rise to a similar shaped curve to the one produced by the exceedingly complicated UK tax code:

There are a few key things to note here:

The effective tax rate for someone earning £17,000 per annum is 0% - they are paying tax at 47%, which is £7,990, but they are receiving a Universal Basic Income of £8,000, so the net effect is that they pay no tax.

Anyone earning less than this has a negative effective income tax rate – someone earning £10,000 per annum will be paying £4,700 in tax, but receiving £8,000 in Universal Basic Income, for a net income of £13,300, or a tax rate of -33%.

At about £31,000 per annum the two tax codes result in about the same amount of tax. Under the UK system, you get the first £8,400 untaxed, between £8,400 and £11,850 is taxed at 12% for £414, between £11,850 and £31,000 is taxed at 32% (20% plus 12%) for £6,128, giving a total of £6,542 or an effective tax rate of 21.1%. Under the hypothetical system, all £30,000 is taxed at 47%, for £14,570, and then Universal Basic Income of £8,000 is received, giving a net tax bill of £6,570, or 21.2%.

Above this point, the hypothetical tax code does result in a higher tax rate. Someone earning £40,000 per annum would see their effective tax rate increase from 23.6% to 27.0% - an increase in tax of £1,378, or £115 per month, while someone earning £80,000 per annum would see an increase from 32.0% to 37.0% - an increase in tax of £4,013, or £334 per month.

The lines are both approaching 47% as incomes increase. Neither line will ever reach exactly 47%, but the impact of the lower tax brackets or the Universal Basic Income become less and less significant as the gross income increases.

With just two numbers, 47% and £8,000, it was possible to define a tax code that is progressive, understandable and fairly similar to the existing UK code. Furthermore, it is difficult to argue that this code is unfair, as it is not punitively targeting high earners with very high tax rates – both numbers apply to everyone, at every income level.

This rather neatly demonstrates the counterargument to the oft raised objection that "Only people who need it should get state assistance", and "paying money to the rich is a waste". When viewed together with the tax code, it becomes clear that a Universal Basic Income is effectively a reduction in tax for anyone with a positive effective tax rate. If it is deemed that the rich are not paying enough tax after factoring in the Universal Basic Income, then the tax rate can be increased, but in this scenario, anyone earning over £31,000 has already seen a net tax increase, so these people are definitively not "being paid extra money". The impact of a Universal Basic Income on anyone with a positive effective tax rate (here, people earning over £17,000) is simply to change their effective tax rate. Certainly, they will be receiving payments from the government, but they will also be paying taxes, so it will be the change in the total amount of money they take home at the end of every month that they care about.

The benefit for the government in operating this way is simplicity – by paying everyone in the country, and taxing everyone in the country, there is no need for entire government departments devoted to means testing, nor is there a need to perform a calculation any more complicated than multiplying two numbers together, to work out how much tax to charge. It might seem inefficient for the government to be paying someone money only to recoup it back as tax, but transferring money is an incredibly simple and quick thing to do. Checking that a calculation is correct, and verifying that exactly the right amount has been received or paid is the thing that takes time and effort, which makes it a good idea to reduce the amount of complexity in the calculations as much as possible, even if it does mean doubling the number of transactions.